“On the basis of some information and a little bit of guesswork you journey to a site to see what remains were left behind and to reconstruct the world that these remains imply.” Toni Morrison, “The Site of Memory”

Charlottesville, Virginia. April 3, 2018.

Eight months after a well-organized army of torch-wielding white supremacists marched through the grounds of the University of Virginia, several black fraternity and sorority members assemble near an informal yet iconic gathering spot on campus for the filming of our latest project, Black Bus Stop. Under the glare of the moonlight, the students sway to the rhythms and memories of the past. The Kappas shimmy, the Omega Psi Phi brothers hop, and the sisters of Sigma Gamma Rho prance with unshakable confidence. Shouts of approval pierce the air as the students repossess hallowed grounds. Their sinuous movements produce a beautiful mélange of history and fantasy.

Much to our delight, the nocturnal shoot is an overwhelming success. After three hours of filming, the crew packs up the equipment, while the student actors dash off to their next round of extracurricular activities.

Thanks to the invaluable contributions of our students and the brilliant choreographer Marjani Forte, we are much closer to the completion of our latest installment of the film series, Black Fire.

Launched in December 2011, Black Fire currently consists of eight short films, Sugarcoated Arsenic, U. of Virginia 1976, We Demand, Fastest Man in the State, 70kg, How Can I Ever Be Late, Black Bus Stop, and Hampton. Though individually distinct in their formal qualities, these films reflect our deep interest in the interiority of black life, particularly those formal and informal spaces where African Americans communed, hobnobbed, prayed, loved, quarreled, reconciled, and moved on. Within these spaces, our gaze fixates on the epic and the quotidian, the sacred and the profane, the individual and the collective.

In the Beginning

Shot during the last week of October 2012, Sugarcoated Arsenic stars Erin Stewart as Vivian Gordon, the director of UVA’s Africa American Studies program from 1974 to 1980. Inspired by Horace Ove’s documentary Baldwin’s Nigger, the opening scene features Gordon delivering a powerful address to an intimate group of black students. Moving across time and space, Gordon recalls her formative years in segregated Petersburg, reflects on the grace, humility and brilliance of the historian Luther Porter Jackson, and outlines the particular challenges and opportunities facing African Americans in the post-Civil rights era. Her passionate address captures what literary critic Houston Baker calls the poetry of impulse: “black articulateness and lyricism in the very face of violence, catastrophe, rejection and exploitation.”

Closeups of both Vivian Gordon and the receptive students underscore beauty and necessity of intergenerational exchange.

At the film’s 9 minute mark, the focus dramatically shits to two stylishly attired students competing in a lively game of foosball. Inspired by a 1974 photograph of two foosball players, the scene underscores the importance of pleasure in building and sustaining community.

Other casual moments captured on film include African Americans playing cards, discussing books, and hobnobbing at a cocktail party. All of these scenes are “reenactments” of stunning photos of African American students, faculty, and workers during the 1970s.

Even during these moments of leisure, Sugarcoated Arsenic never loses its political edge as the stately voice of Vivian Gordon offers political instruction and ancestral wisdom.

Drawing from both the visuals and the sonic innovations of the Black Power Movement, the film closes with students marching and chanting parts of the Black Panther Party’s rallying cry, “Revolution Has Come!”

Filmed during the week of Superstorm Sandy, Sugarcoated Arsenic was a labor of love. Not just in terms of the weather conditions, but also in terms of the extensive archival research involved in crafting the scenes. During the research process, we unearthed unedited footage of protest marches from 1969 and 1970, reel-to-reel audio of antiwar protests, and videotapes and cassettes of noted Black Studies scholars. And then there were the hundreds of photographs from the 1970s and 1980s, visual evidence of the ingenuity, resourcefulness, and sheer brilliance of UVA’s black community.

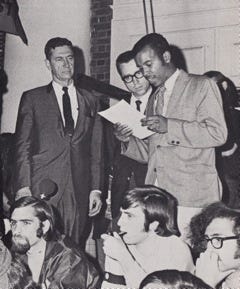

Out of this treasure trove of archival material emerged the foundation of our next film, We Demand. Shot in the fall of 2014,We Demand turns attention to the antiwar movement and focuses onRoebuck, a Philadelphia-born African American who enrolled in UVA’s graduate program in 1966. Upon his arrival on campus, he immersed himself in student politics, eventually becoming the president of the school’s student council. Several weeks after his election as the council’s first black president, political upheaval engulfed the university as youth activists erupted in protest over the Ohio National Guard’s brutal murder of four coeds at Kent State.

During the first two weeks of May, 1970, students boycotted classes, occupied buildings, and pushed the University’s president, Edgar Shannon deeper into a heated confrontation with elected officials in Richmond. Feeling as if the entire system needed to be overhauled, progressive students presented administrators with a list of demands that included eliminating ROTC and research sponsored by the military, removing all law-enforcement officials from the grounds, and “accepting 20% as a goal for the enrollment of black students throughout the University.” The final demand addressed the labor issue: “We demand that President Shannon express public support for the right of University employees to strike and bargain collectively.”

Diplomatic but principled, James Roebuck faced the daunting task of mediating the brewing conflict between his colleagues, the University’s president, and a seemingly trigger-happy state all too ready to rely on force to quell dissent. Fortunately, he had the support of the somewhat sympathetic Edgar Shannon who in addition to condemning the state police for its excessive use of force expressed outrage at “the continued alienation of our young men and women owing largely to our nation’s military involvement in Southeast Asia.”

Searching for greater insight into this complex political moment, we journeyed to Philadelphia in the summer of 2014 for a meeting with Roebuck (who since the 1980s had represented the 188th Legislative District (West Philly) in the Pennsylvania House of Representatives). With vivid detail, Roebuck described the tumultuous aftermath of Nixon’s invasion of Cambodia and the Kent State murders. His reflections, along with newspaper clippings, antiwar memorabilia and placards, surveillance video, audio, and photos, inspired our next film, We Demand.

Released in 2016, We Demand features Ricky Goldman as James Roebuck, Richard Warner as Edgar Shannon, and Ryan Leach as student activist Tommy Steele. In the film’s opening, we see Roebuck and Steele typing a list of student demands. We Demand then segues into President Shannon and James Roebuck preparing for their respective meetings with elected officials in Richmond and Washington, DC. The closing scene finds Steele and Roebuck on the open road, reflecting on the last few days. During the drive back to Charlottesville, Roebuck recounts his journey into activism, reminiscing fondly on the political lessons he received from his mentor, the Reverend Marshall Shephard, his organizing work with the Philadelphia NAACP as an adolescent, and his involvement in the civil rights movement during his undergraduate years at Virginia Union.

Moving from the world of antiwar activism to the sports arena, our next film turned attention to aesthetics and politics of athletic competition. In Fastest Man in the State, Charlottesville native and UVA alumnus Kent Merritt waxes eloquently on his experiences as one of the university’s first four Black scholarship athletes. Along with recounting his experiences with racism during the early days of integration, he revisits the particular challenges endured by his teammate and fraternity brother, Harrison Davis, who in 1971 took over the quarterback position. If nothing else, Merritt’s recollections remind us that the sports arena has never been a politically free zone. His bittersweet memories of the entrenched racism on America’s college campuses, along with his reminders of how he and his black teammates found solace in each other, take on deeper meaning in our current moment, when many athletes have intensified their call for systematic change in this country, particularly around issues related to state-sanctioned violence against African Americans.

This film benefitted immensely from the generosity of Merritt, as well as the contributions of our student actors, who delivered fantastic performances.

Sly Comes to Charlottesville

Forgive us in advance for the lengthy introduction to our next film, How Can I Ever Be Late, but it is necessary to discuss, briefly, the event that inspired its creation.

On Friday night, November 30, 1973, one of pop music’s biggest acts, Sly and the Family Stone, performed at University Hall in Charlottesville, Virginia. Taking the stage one hour later than scheduled, the iconic band opened with the revolutionary funk anthem, "Thank You (Falettinme Be Mice Elf Agin).” Spirits were high as the crowd sang the chorus in unison:

I want to thank you falettinme be mice elf agin

Sly and the Family Stone got off to a strong start, but tension left over from the band’s late arrival surfaced throughout the concert.

On one occasion, Sly stopped the show for what he viewed as the crowd’s disrespectful behavior during the band’s performance of “Que Sera Que Sera.”

“That’s my sister [Rose] over there who’s trying to sing,” a frustrated Sly complained to the audience. “You’re hurting my feelings. We don’t want to sing anything that you don’t want to hear.”

The situation was tense.

But according to one attendee, William Bruckner, Sly had misinterpreted the situation.

The issue was not Rose’s performance but rather the refusal of fans in the front rows to sit down.

Combined with their frustration over the lackluster opening act and a late start, Brucker and others were infuriated to have “the star group completely hidden from view by the people who already had the best seats in the house. There was no magic for those of us with the misfortune of having to find seats further back.”

Despite these issues, the concert definitely had its high points, most notably, the band’s fiery rendition of “I Want to Take You Higher.”

“Peace signs and clenched fists filled the air as Sly surveyed the mass of people, totally under his spell,” Andy Ballentine raved in his concert review.

What Ballentine did not mention was the brewing controversy over the band’s payment.

On December 3, UVA’s student newspaper (The Cavalier Daily) informed readers that Sly would be docked for his late arrival.

The concert promoter PK German, a student run group that brought some of the biggest names in popular music to Charlottesville, refused to pay the full price for Sly’s services.

According to one university official, PK German’s stance was justifiable: “We felt the flat fee should not be paid in full and we put into effect a clause in our addendum to withhold a sum of $2,000 for the 40 minutes to an hour that the band seemingly refused to go on stage…When a new check is prepared by the Bursar’s Office, PK German will pay the contracted price, minus $2,000.”

By the time of his visit to Charlottesville, Sly’s issues with lateness (and no-shows) were well known. In fact, in its concert review, which was quite favorable, the Cavalier Daily noted that many students “didn’t show up because they thought Sly wasn’t going to show up .”

Of course, thousands did show up.

Why?

Because Sly remained one of the most innovative artists in popular music.

And with the release of Fresh in June, the co-architect of Funk was still very much at the top of his game.

As Stephen Davis wrote in his Rolling Stone review:

“Fresh is Sly’s new direction for 1973, a potpourri of styles, new musical attitudes and futuristic black trances. In a sense it completes the cycle that every successful pop musician undergoes, from a strict Top 40 mentality to a more complex and creative (yet still commercially viable) maturity. The Family Stone’s early records were classy and exuberant exhortations to Spirit; we were urgently advised to dance to the music, to stand. You can do it if you try…Fresh is a growing step for Sly — out of the murky and dangerous milieu that infused Riot and into a greater perspective on his own capacity to make music a positive form of communication. In its own sense, and on its own terms, it is his masterpiece.”

There’s so much more to say about Fresh, as there is so much more to say about Sly’s concert in Charlottesville .

The Cavalier Daily’s coverage of the event is a topic in itself. So, too, are some former students’ memories of the event.

Over the years, several African Americans have told us some pretty interesting stories about not just the concert but Sly’s arrival to the city.

So we decided to take the tarmac arrival of Sly and the Family Stone to Charlottesville as its reference point for How Can I Ever Be Late, the six film in our series.

The Black Red Carpet

The previously mentioned “Black Bus Stop” was shot in 2018. For many African Americans who attended the University of Virginia during the post-Civil rights era, the Black Bus Stop is sacred ground. It represents their efforts to affirm their humanity and sense of personhood and built transcendent spaces of communion.

Now the BBS doesn’t have an “official founding date” but by most accounts it became a popular spot in the late 1970s, the decade when African Americans built the institutional infrastructure of what some refer to as “Black UVA.” The Black Bus Stop, located on a central part of campus and not too far from the Business School, was incredibly popular during the 1990s, the peak years of black enrollment. At the popular hangout, students could be seen talking politics, joking with each other, playing music, setting up dates, etc. One UVA alumnus called it "the Black Red Carpet."

Black Voices

The serious with which black students regarded the Black Bus Stop became apparent to University administrators in the fall of 1997, when the University Transit Service changed the route and temporary suspended the stop at the BBS. Over the course of a month, students engaged in protests, sending letters to administrators, holding town hall meetings, and raising questions about the University’s commitment to the black student body.

Set in the 1970s, Hampton follows Black Voices, a gospel choir based at the University of Virginia, as it prepares for a performance in Hampton Roads, embarks on a two-hour bus ride to the concert venue, and then returns to campus after a triumphant performance. With a particular focus on the bus driver (Sandy Williams), the film captures the wide range of processes, relationships, emotions, and formal gestures operating in African American gospel music.

The script for Black Voices draws inspiration from the gospel aesthetic, as well as interviews of two UVA alumni: Chavis Harris, a charter member of Black Voices, and the late Debra Saunders-White, the former president of North Carolina Central who attended UVA between 1975 and 1979. In their interviews, Harris and Saunders-White detail the centrality of Black Voices in helping them navigate the challenges of the University. In explaining why he and his colleagues selected Black Voices as the choir’s name, Harris pointed to the cultural ethos of the Black Power era, as well as the political atmosphere of UVA. He noted: “There were times, like if you were walking on the grounds at night and you were an African American male, and if you were studying and decided to take a break and take a jog like students do all the time, you were probably going to get followed by the university police and stopped.” Such encounters intensified Harris’ and other black students’ desire for institutional spaces that would not simply challenge white racism, but also affirm their humanity. In many ways, Black Voices was such a space not just for those in the choir, but also those students who appreciated gospel as an art form. This was the case for Saunders-White (pictured below), who conveyed to us the story of Black Voices’ bus trip to Hampton, relating how the University’s decision to allow the choir to use one of its buses was the first time she felt as if she actually “belonged” to the University.

With all our film projects, we hope to capture how local and national histories are intertwined. We also hope to provide additional opportunities for our students to further develop and express their artistic gifts and craft, see the value of interdisciplinary work, and contribute to the retelling of UVA’s rich history. Our film participants include students from our classes in cinematography, history, and Black Studies. So in addition to making art, we are trying to provide a model for our students. We want them to understand the beauty of collaboration, to appreciate what can be gained from learning together, holding each other accountable, and blending one’s talents for the benefit of the collective.

In other words, we want them to know the art and beauty of peer pressure.